“Don’t Look Up” doesn’t reach its potential

“Don’t Look Up” is one of the most controversial movies of the year. Climate activists and Bong Joon-ho loved it (it was shockingly ranked as number two on his favorite movies of the year list). Cinephiles and most critics hated it. Why the great divide?

March 15, 2022

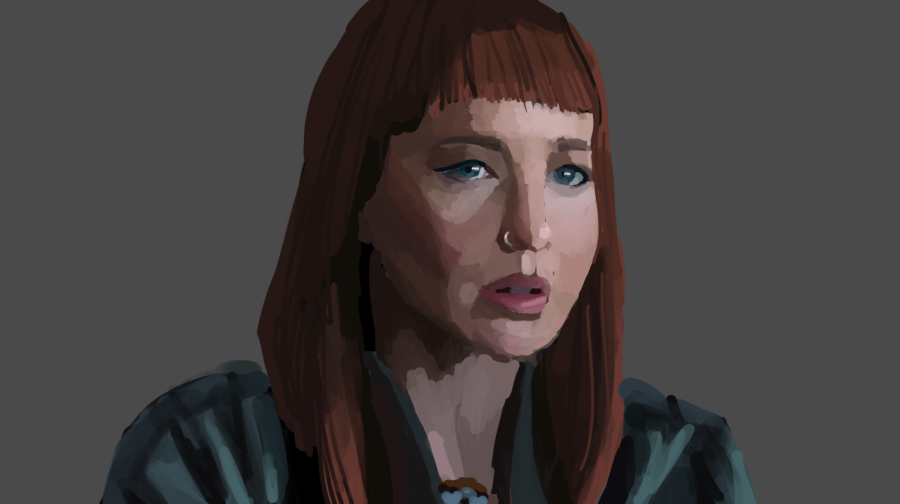

Zephyrus Arts and Entertainment Editor Hannah Owens Pierre examines each Oscar Best Picture nominee in a countdown to the awards ceremony on March 27

“Don’t Look Up” is one of the most controversial movies of the year. Climate activists and Bong Joon-ho loved it (it was shockingly ranked as number two on his favorite movies of the year list). Cinephiles and most critics hated it. Why the great divide?

It comes down to the way “Don’t Look Up” executes—or fails to execute—satire. The movie, directed under the distinctive vision of Adam McKay, known for work on “The Big Short” and “Vice,” is about a group of astronomers trying desperately to get the world to care about an incoming apocalyptic asteroid crash, to no avail. Instead, the newscasters laugh, the president lies, and the business tycoons focus on exploiting resources from the comet instead of preventing extinction. It is all too obvious that McKay’s real subject matter is climate change and the way the world has collectively ignored its existence for short-term material gain.

That being said, there are a few crucial discrepancies between McKay’s imagined apocalyptic scenario and the real, pressing threat of global warming that prevent it from sticking its landing.

Firstly is the issue of how the existential threat came to be. It is no secret that climate change is anthropogenic, that is, caused by human activity; whereas the comet said to collide with earth in “Don’t Look Up” originates strictly by chance. There is no condemnation of the world’s inhabitants to be had because there was seemingly no way to have prepared for or prevented the scenario. This is such a glaring error in the plot that it is startling no one seemed to realize it prior to production.

Then there’s the problem of the solution to the threat. For “Don’t Look Up,” all that’s required is for the President to agree to shoot a nuke into the sky. The fix for climate change is, quite obviously, a bit more complicated than that. It is one that requires the sustained effort of every individual on the planet, not just the might of one powerful politician.

By ignoring the complexities of the climate crisis, “Don’t Look Up” misses the opportunity for a more nuanced and thought-provoking film. It is easy to watch McKay’s work and come away with the conclusion that climate change is the fault of evil, greedy billionaire caricatures like the one Meryl Streep portrays.

Poorly thought out analogies aside, “Don’t Look Up” is so self-important that it doesn’t seem to realize how corny it is. From excruciating “memes” that feel like a parody of the younger generations only a Facebook boomer could produce to insultingly stupid dialogue, “Don’t Look Up” has almost nothing to offer in the way of humor.

The best thing that can be said about the movie is that, like McKay’s other films, it is incredibly entertaining. Like a monstrously bloody car crash on the side of the road, it is difficult to look away from. McKay’s directing, though overly flashy, keeps you hooked on the screen combined with a magnetic score.

“Don’t Look Up” has an important story to tell. But there is something to be said about biting off more than one can chew. Even worse is doing so obnoxiously and then vomiting on your shirt. There are interesting, well-made films about the threat climate change poses—“First Reformed” comes to mind—but “Don’t Look Up” isn’t one of them.