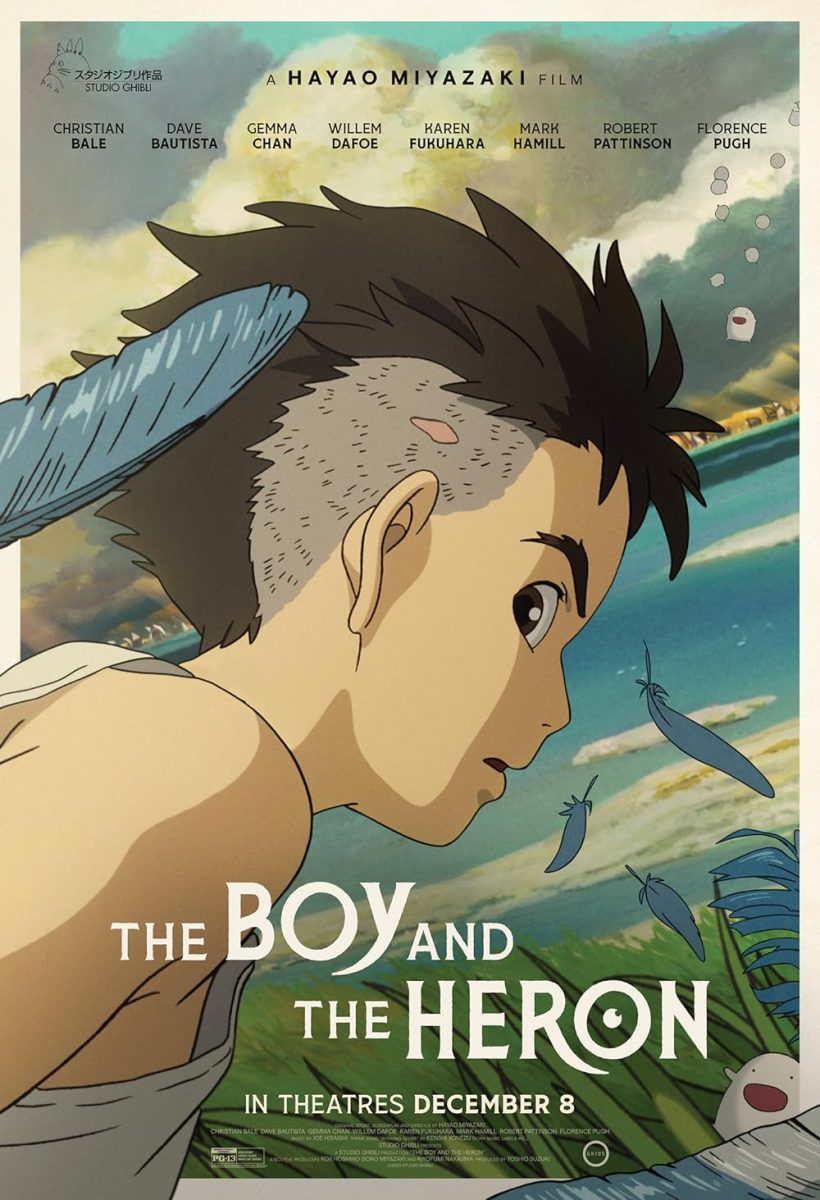

Studio Ghibli director Hayao Miyazaki’s latest film, “The Boy and the Heron,” is a powerful yet obstinate exploration of the nature of grief. Due to its complex nature, the film demands at least two watches to get its message across.

The movie follows Mahito, a boy who lost his mother in a hospital fire during World War Ⅱ, as he tries to adjust to his new stepmother, Natsuko, who happens to be his mother’s sister. One day, Natsuko disappears into an ancient tower, and it falls to Mahito to save her. Guided by a mysterious gray heron, he discovers a world full of spirits, gods, and man-eating parakeets.

The movie starts off strong, grounded in the harrowing reality of PTSD. Beginning with a flashback to Mahito’s mother’s death, we watch as he races through the streets, the air punctuated with the sharp droning of an air raid. The animation mirrors his panic, the figures around him twisting into almost demonic visages, his mother crying out for him. When he is visited by the gray heron promising that his mother isn’t dead and he can rescue his new one, he jumps at the chance, ignoring all obstacles in a desperate attempt to rescue those he loves. This sets the scene for the theme of the movie: letting go.

The film’s central focus is Mahito’s relationship with his stepmother Natsuko, and it portrays the dynamic in a confusing and somewhat roundabout way. Initially, Mahito treats her with casual disdain, only remarking she looks exactly like his dead mother, not caring that she is pregnant with another baby. When offered the chance to follow the gray heron into the other world, he admits he is only doing it because of the possibility his old mother might still be alive. Indeed, she is, albeit a younger version of herself around Mahito’s age. She also has fire powers, seemingly related to her death in the hospital bombing. However, both her age and her abilities are never explained, as she immediately agrees to help search for her sister or rather Mahito’s stepmother.

When Mahito learns that his stepmother is in a delivery room, giving birth to her baby, he takes it upon himself to convince her to go back to his world. Arriving in the room, he fails to consider how she feels about returning with him. Even before Mahito lays eyes on her, the stone walls of the room crackle with electricity, warning him not to approach. When he does finally speak to her, she says she hates him, possibly because she still has guilt over losing her sister and having to care for her dead sister’s son. The fact that her sister is alive in this new world might contribute to why she doesn’t want to leave. Perhaps because of the closure he gained from seeing his mother again, Mahito agrees to accept Natsuko as his new mother, and they start the journey back together. This scene is a bit jarring, as we don’t see any growth from Natsuko around the hatred that was present before, and it is never explicitly stated what caused Mahito’s change of heart. Despite this, the reunion of stepmother and son feels genuine and believable, although that could be attributed to the moving voice acting, not the script.

Lack of character development notwithstanding, what the movie truly excels at is its themes. The new world we enter has been built by Mahito’s great-grand-uncle, who wants to create a new reality, full of peace and prosperity. When we meet him for the first time, he is stacking blocks on top of each other, which need to be rearranged every two days for the world to continue to function. On top of this, per his deal with The Stone, the source of his magic powers, only a member of his family can stack the blocks, otherwise, the world will fall apart. The ridiculous conditions required to maintain the world’s existence highlight how much easier it would be to just let go of these unrealistic expectations.

The great-grand-uncle is also blind, so he wants Mahito to succeed him. When he brings Mahito the blocks, Mahito sees that these blocks are full of malice, and so cannot be stacked. All of this time, his great-grand-uncle had been working with defective blocks, unintentionally perpetuating harm into the world.

We see the effects of this blind faith in the blocks manifest in the various animals. The great-grand-uncle has dragged animals from our world into his in an attempt to make it more beautiful: pelicans and parakeets. However, the pelicans are not able to survive on fish like they normally would. Instead, they have to eat the souls of soon-to-be humans, called Warawara. A similar phenomenon occurs with the parakeets. Instead of colorful, majestic creatures, they have turned into apex predators. They are able to eat anything, form their own monarchy, and are in constant conflict with Mahito’s great-grand-uncle, fighting to be the masters of their world. The great-grand-uncle dismisses their plight, as he wants to stay in control. This desire is why he made the deal with The Stone. By believing so strongly in his dream of creating a perfect world and his own abject rightness and ignoring the obstacles, the great-grand-uncle has effectively doomed his own creation, only prolonging its suffering by having Mahito take his place. Having moved on from the death of his mother and accepting his new present, Mahito sees this and refuses to continue perpetuating his great-grand-uncle’s failed dream. The message is clear: one has to be able to move on, otherwise those around them will suffer.

Karen McVann • Jan 11, 2024 at 10:07 pm

You are an amazing writer Finn. I saw that movie and was totally confused by all of the switching around. For me, it was hard to tell if it was pre or post World War Two. You deciphered and extracted much more meaning than I. I admit, seeing it again might have helped, but I wasn’t willing to sit through such a long movie again.