Each day, a few thousand people enter and exit the doors of Edina High School. Within the building is the continuous movement of students, faculty, and administration, each with different goals in mind. As concerns across all sectors, from the hectic parking lot to the abuse of technology in classrooms, have grown more prominent, the EHS administration established new policies and enforcement for the 2024–25 school year.

Many of these policies are years in the making, involving teacher committees, student group input, and heavy discussions with the Edina School Board. “It boils down to teachers and administration all want[ing] students to be in class and to be successful and we feel like these practices will increase the likelihood of that for a lot of students,” Assistant Principal Mike Pretasky said. “There’s still the learning curve of what these policies and procedures look like played out.”

Though the Edina Public Schools District prides itself on “achieving excellence,” the changes in procedure are being met with starkly different opinions and reactions as teachers and students alike work to adapt to the new school environment.

“Away,” “gray,” and “okay”: EHS’s new tiered device system

Earlier this year, the Minnesota state legislature passed a bill requiring all school boards in the state to adopt some policy clarifying student cell phone usage in their district by March 15, 2025. EPS had been working toward a new policy addressing all device usage prior to the passage of the bill and finalized it over the summer.

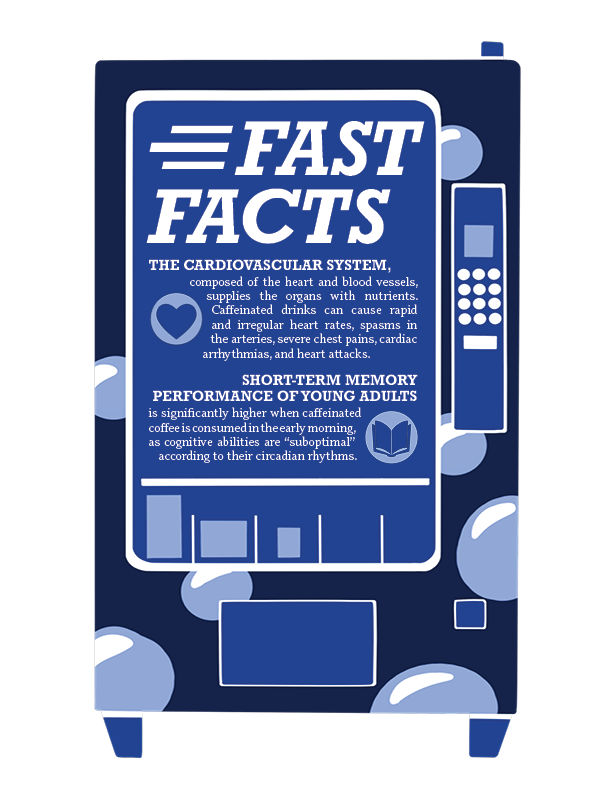

Human Anatomy and Enriched Biology teacher Jeff Krause worked to resolve the distracting nature of cellphone use in his classroom.

“Spring of 2022 I started doing research, looking for articles, research projects about cell phone use, the prevalence of use, and the impact on learning,” he said. “That [research] progressed into finding out that maybe these devices were not so positive for learning, student attention and achievement.”

Krause’s additional efforts include conducting his own staff surveys around cell phone use, producing a proposed cellphone management plan, creating the current cell phone policy, and banning device use in his classroom.

“As far as cell phones in my classrooms, I’ve noticed over the years that students were increasingly distracted with cell phones, so a couple years ago I decided to take matters into my own hands and prohibit it,” Krause said.

This year, the district introduced a new device policy that follows a tier system. The tier system consists of three tiers: “away,” “gray,” and “okay.” Tier one, “away,” is the default for all classrooms and devices; school and personal technology should be out of sight always. The next tier, “gray,” is a mix between tier one and three, as devices are allowed out at a teacher’s discretion. Finally tier three, “okay,” allows devices to be used at a student’s discretion during class time.

The tier system and new policy were developed with the help of administration, students, teachers, parents, and student groups such as the Cell Phone Task Force committee of the Student Senate. “A lot of the adults wanted an absolute ban so the tiered approach was a compromise. The main goal was to provide support for teachers,” senior and Student Senate member Indra Khariwala said.

The tier system allows all teachers to follow the same structure and be consistent. “I think [the tier system] is working well so far because it’s universal. All teachers are doing it because teachers are talking between each other on how to manage it. If it’s enforced school-wide, it’s going to work. If certain teachers don’t follow it, then it’s not going to work,” Latin teacher Emese Drew said.

Some students feel the device policy does not provide additional structure. “I did not go on my phone much before, but I feel there is some redundancy in needing to put the phone in the backpack,” sophomore Eli Aberle said. “I know a lot of my friends are somewhat irritated at the new policies, just because, each teacher had their own policies with phones.”

Khariwala believes the current policy is just the first iteration with more areas to explore, especially in terms of safety. “It kind of became an issue of ‘should there be other ways to communicate with your child that don’t involve them using a phone?’ but that’s a whole other thing. It’s all kind of gray area,” she said. “I’m sure with input from parents and other adults, and as research comes out, they might reopen the discussion. But, I think for now, that’s what they’ve landed on.”

EHS parking shifts: student and staff division, pass price increase, and ticketing surge

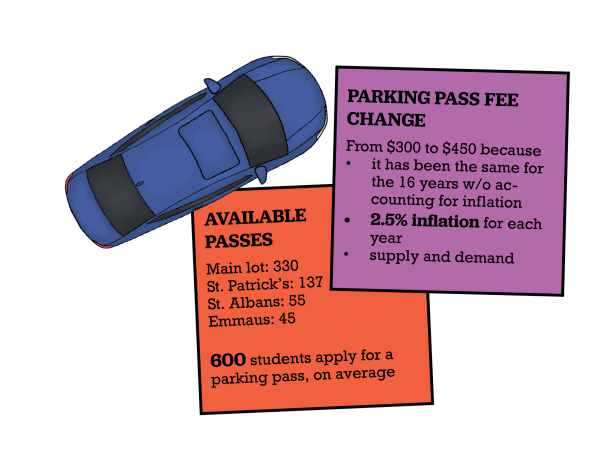

Solving the issue of EHS parking has proved to be an extremely difficult endeavor for several years. With an average of 600 students applying for a parking pass, the spots supplied aren’t able to meet the demand. There are around 567 student passes available each year: 330 for the EHS main lot (Edina Performing Arts Center and outside Door 6), 137 spots at the Church of St. Patricks, 55 spots at St. Alban’s Episcopal Church, and 45 spots at Emmaus Road Reformed Church.

The use of church lots helps compensate for the limited amount of spots provided for students in the main lot. “A lot of people worked hard to get those church lots before me and that was a big collaboration,” Dean of Students Jeff Pope said. “The reality is that without those church lots, our process would be way harder for parking.”

For the 2024–25 school year, the EHS main lot was divided into staff and student sections to ensure parking spots for both parties. “After talking with a number of different people throughout the year, parents, students, and staff members, [it was decided] that [staff and student zones] was the easiest thing to do without it being too overwhelming for everyone all at once,” Pope said.

Even with the new lot changes, many students are still experiencing frustrations with school parking. “The fact of the matter is that most of the teachers stay after school, wait for the rush traffic to be gone, or are helping students with office hours. So for them to get the front spots [in front of Door 5] just doesn’t make sense because lots of students have after-school activities, jobs, or commitments,” senior Summer Wang said.

“I think a little too much [main lot] parking was allotted to the staff over the students. There’s more students than staff, therefore the staff shouldn’t get almost an equal part of the parking lot, because I drive by and notice that there are plenty of spots open in the staff area, whereas students are struggling to find spots,” senior Kate Maloney said.

2024–25 also brought forth a 50% price increase for main lot passes: $300 to $450. The price of main lot passes hadn’t been increased in 16 years without accounting for 2.5% inflation each year.

Ticketing was an issue last year at EHS, with 559 tickets being issued for the 2023–24 school year. Seniors were charged with almost half of the total tickets, at 220. However, this year, ticketing may be even more extensive, with ticket projections exceeding those of 2023–24. As of Sept. 5, the school has already issued 20 tickets. If this trend continues, the school will issue 900 tickets for this school year.

Universal bathroom passes to reduce students in the halls

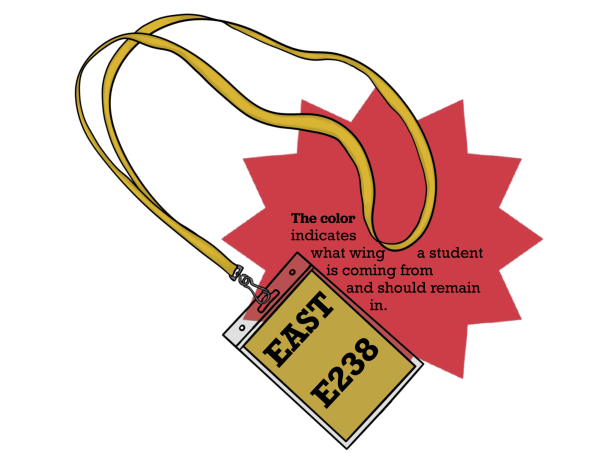

For the 2024–25 school year, every EHS class has implemented a color-coded five-minute bathroom pass system, permitting one student to leave at a time and stay in their designated wing of the building to use the restroom.

Last year, multiple classrooms including world languages, Physical Earth Sciences, and fine arts piloted the use of bathroom passes for freshmen classes.

“In higher years, sophomores, juniors, and seniors sometimes would abuse the privilege of going to the bathroom,” Drew said. “I thought this was a good process to help the students learn the discipline of staying in class with only one person out at a time.”

Teachers have found the passes helpful as they no longer need to spend energy figuring out who is out of the classroom. Additionally, according to Pretasky, this provides a safety element “in that in the event of an emergency, we are responsible for every single student and we need to know where every single student is.”

Some students found difficulty when peers took the bathroom pass for extended periods of time. “[It] can make it so that students who actually need to go to the bathroom aren’t getting the chance to go to the bathroom,” Aberle said.

In the middle schools, a digital bathroom pass system was implemented in 2022. Through a Chromebook app, students of South View Middle School were given three six-minute passes a day. “It was just very limited and towards the end of the day, when you were out of passes, you couldn’t go,” freshman Ella Basile said.

EHS considered following similar protocols before settling on the current lanyard system. For freshmen, the bathroom passes at EHS are far more lenient compared to the system at the middle schools. “The teachers are super flexible and when you have to go, you have to go, so you can go however many times you need to go. Especially in a seven-period day, I’d only be able to go three times a day at South View, which sucked in reality,” Basile said. “From all the ninth graders that I’ve talked to, everybody thinks it’s so much more flexible and so much easier to handle and it’s not as stressful.”

Others reflect positive sentiments about the effectiveness of the new system.

“Since it’s universal in the whole school, students learn it very fast that okay, if it’s expected in the whole school, then that’s what it is and they just don’t fight me on that,” Drew said. “Of course, what we want to see is less traffic in the hallways and less partying in the bathrooms.”

Reforms to Policy 503 in the wake of growing absenteeism

Since COVID-19, the EPS District, alongside many other districts, has seen a sharp increase in chronic absenteeism, which is typically defined as missing at least 10% of the school year for any reason. “We started talking about [absenteeism] about two years ago, but it just didn’t improve since COVID. The attendance probably actually got worse,” Assistant Principal Jenny Johnson said.

According to the American Enterprise Institute using ED.gov data, the EPS District’s number of chronic absentees rose from 5% in 2020 to 21% in 2023.

In response, Policy 503 of the District Policy Manual was revised on April 8. The last time the policy had been changed was in 2018. The most significant change at the high school level is in Appendix I, altering the responses to focus more on issuing continuing truant letters with Hennepin County and creating intervention plans with habitual truants.

“Our staff really want students to be in class, so we as a team with continuous improvement, need to reflect on ways in which we can ensure that our staff is feeling supported,” Assistant Principal Jenn Carter said.

The change most students have seen in effect is how the school approaches make-up work, now explicitly stated in Policy 503 that for any unexcused absence, students may “make up missed work for up to 75% or equivalent.”

For excused absences, a student has two school days per day of excused absence to make up work for full credit. Junior Ava Leddick noted that there was clash between peers and teachers on the language of the policy. “Some are saying it is two days from the time you get back,” she said.

Previously, the opportunity to make up work depended on the class. “You probably have a teacher that handles late work this way and a teacher that handles late work that way; it gets kind of confusing, right? Because you’re trying to navigate all these different sets of rules,” Carter said. “For the first time in the time that I’ve worked here, we said to teachers, this is something that we need to be uniform on.”

Leddick appreciated this upfront approach teachers took at the beginning of the school year. “I think it’s better that it’s more unified because you don’t have to go and argue with each teacher,” she said.

This follows a greater trend of transparency through collaboration between teachers and administration, finding places where they can be more aligned with established School Board policies.

Another major change in approach is seen in the different advisory structure shifting from a separate class with the same advisor for all four years to an extension of students’ second-period class. “We actually had a staff forum where people were able to weigh in on that,” Carter said. “There were a lot of students that weren’t coming to advisory or had appointments during that time and it was kind of a disruption.”

“There were teachers that didn’t feel super connected because they didn’t have the students from advisory in class, so that relationship was sometimes harder because you don’t see the students in your advisory but once a week,” Pretasky said.

Leddick saw this issue in her previous advisory. “I did not take any sort of class that she taught, nor was I even really in that realm of the school ever and just any questions I brought to her, she wasn’t really capable explaining because she didn’t have any experience with, so it is kind of better to have a guaranteed [teacher] you have class with,” she said. “[Now], we run through everything, it’s shortened, and then my second hour is my math class, so you kind of just have extra time to work on homework.”

The current advisory model aims to focus on college and career readiness as well as social-emotional learning. “That involves a curriculum which can speak to different grade levels depending on what the topic actually is,” Pope said.

The EHS administration hopes that these broader changes in attendance-related approaches will have lasting effects. “You can build good relationships with your teachers if you’re in class, which then enhances your learning, which then enhances your social and emotional [abilities],” Johnson said. “All of it ties together but really the cusp of it all is that students are present for the learning and then teachers are present for the students when they’re in their class.”

This piece was originally published in Zephyrus’ print edition on September 26, 2024