When Edina High School math teacher Katelyn Strauss went to a specialist for consultation on jaw pain three years ago, she was unaware of the connection of the injury to caffeine. “I couldn’t get through the day without this horrible pain, and one of the first questions they asked me was what’s my caffeine intake,” Strauss said. “I showed them my Yeti and it’s something like 16 fluid ounces. I usually drank two or three of those a day and they were like, ‘Yeah, you need to get that down to one.’”

Her diagnosed jaw condition, known as temporomandibular disorder (TMD), causes overtension in the jaw that leads to headaches and toothaches, and though the condition is not fully attributed to caffeine intake, it may impact symptoms. “I’m no doctor, but [TMD] is worsened when you have more caffeine because your body has more energy and it causes some anxieties and it can cause your muscles to clench more,” Strauss said. “So it’s causing the muscles in my jaw to clench down and it’s creating pressure there.”

EHS provides a wide variety of caffeinated beverages throughout the cafeteria and vending machines, including CELSIUS, Bai, and BUBBL’R. The accessibility allows convenience in purchasing caffeine, creating a causal purchase for the student body that may have underlying effects.

A medical lens to caffeine intake

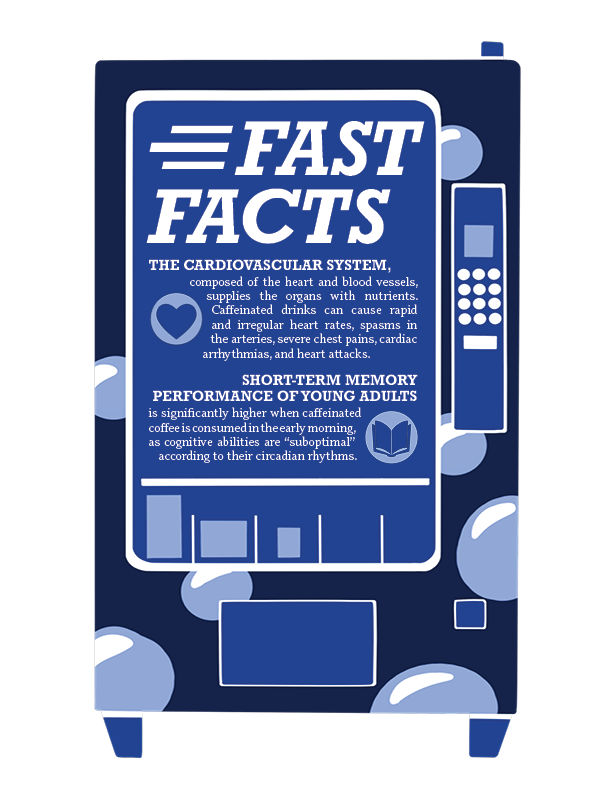

Despite its harmless appearance, caffeinated drinks endanger the heart, and drinking large amounts of caffeine causes damage to the body. “There isn’t anything such as a safe level of caffeine; we always recommend limiting it as much as possible,” Dr. Jane Chen, cardiologist at the University of Minnesota, said.

Despite its harmless appearance, caffeinated drinks endanger the heart, and drinking large amounts of caffeine causes damage to the body. “There isn’t anything such as a safe level of caffeine; we always recommend limiting it as much as possible,” Dr. Jane Chen, cardiologist at the University of Minnesota, said.

The underlying harm of caffeine may best be seen in 2023, when Panera’s super-caffeinated “charged lemonade” beverages was reportedly linked to the deaths of Sarah Katz and Dennis Brown. Brown, who had high blood pressure, drank three lemonades, as he was unaware of the lofty amounts of caffeine and sugar, leading to a heart attack. Katz, on the other hand, had an underlying heart condition, and drinking a single charged lemonade caused her heart to beat excessively, sending her into cardiac arrest.

Panera’s charged lemonade contains over 390 milligrams of caffeine—an entire day’s worth of caffeine in a single drink (FDA regulations advise that adults consume no more than 400mg of caffeine per day). These alarming realities shocked Panera customers, as many were unaware of the lemonade’s dangerous potential. “I never knew that much caffeine could kill someone,” junior Katie Lippert said.

Though Katz and Brown’s deaths have caused an uprising around the dangers of caffeine, they are not the only victims, as caffeine has been the long-standing culprit behind many accidental deaths. According to studies conducted by the American Heart Association, more than 40% of calls to the Poison Control Center are related to children under six consuming energy drinks.

Today, many teens, including Lippert, use caffeine as a quick energy source to awaken them in the morning or beat afternoon fatigue. “[Caffeinated drinks] help me wake up in the morning and get me through the rest of the day,” Lippert said. Though they advertise energy, caffeinated drinks may only fuel long-term damage and worsen the current strain of school, extracurriculars, and sports.

According to University of Minnesota Sleep Profession Dr. Bimaje Akpa, many teens are unaware that they have become trapped in the caffeine addiction cycle, in which regular caffeine consumption places increasing difficulty on sleep by reducing the amount of “deep sleep.” “People say that drinking caffeine doesn’t affect [their] sleep because they’re still asleep about the same amount of time, but, really, [their] quality of sleep is significantly lessened,” Dr. Akpa said. With caffeine drinkers retaining less and less deep-wave sleep each night, they continue to turn to caffeine for energy, unaware that it is causing the problem.

This pattern eventually leads to caffeine dependence, where a person retains so little deep-wave sleep that they require caffeine to feel somewhat normal. As a result, they consume more and more caffeinated products but experience minimized effects.

The more a person relies on caffeine, the more difficult it becomes to break the addiction cycle. “Chances are, when you try to stop using caffeinated products, you’re gonna go into caffeine withdrawal,” Dr. Akpa said. Similar to other stimulants, caffeine withdrawal occurs when a person tries to limit a substance their system has familiarized. As a result, they may experience uncomfortable symptoms, including headaches, extreme fatigue, depression, irritability, and difficulty thinking, which Lippert herself has recognized. “ When I do try to lessen my intake, I notice withdrawal symptoms like headaches,” she said.

Though the cycle may seem unbreakable, teens are capable of overcoming caffeine addiction with a gradual approach. “Instead of going cold turkey, you can slowly wean yourself off,” Dr. Akpa said. This means choosing drinks with less caffeine, progressively drinking fewer cups of coffee, or slowly transitioning to decaffeinated beverages. Other non-beverage-related routines may also replace daily caffeinated drinks, including sunlight exposure or exercising in the morning to kickstart body systems.

Dr. Akpa also mentioned that teens can consume caffeine and retain significant amounts of deep sleep by timing their intake correctly. Caffeine metabolization differs from person to person, but all teens require at least eight hours to fully metabolize the substance, and Dr. Akpa recommended that teens cut off their caffeine intake after noon to meet this goal.

Dr. Akpa also mentioned that teens can consume caffeine and retain significant amounts of deep sleep by timing their intake correctly. Caffeine metabolization differs from person to person, but all teens require at least eight hours to fully metabolize the substance, and Dr. Akpa recommended that teens cut off their caffeine intake after noon to meet this goal.

EHS Nurse Beth Gissibl also urges students to be cautious of what they consume as a pragmatic solution. “I don’t know that completely swearing off coffee or caffeine is possible, but trying to be smart and have everything in moderation is possible,” Gissibl said.

Caffeine within the academics spheres of EHS

With the normalization of caffeine in students’ lives, however, many have seen positive impacts of the stimulant on their academic careers. “I think that honestly, [energy drinks] help me stay focused during classes,” senior Tenny Schermer said.

Studies conducted by Johns Hopkins researchers revealed that caffeine can enhance memory and help students absorb new information for more than 24 hours.

Consequently, sophomore Ellie Shipp uses caffeinated drinks to boost preparation for tests. “It makes me cram more and last minute study which is probably not the best for my academics,” she said.

Still, regarding her overall performance in school, Shipp feels that her early introduction to caffeine resulted in a different outcome than others. “I’ve been a caffeine addict since sixth grade, so it hasn’t affected my grades,” she said. Shipp explained that as long as grades had mattered to her, she had been drinking caffeine, leading to an earlier adjustment to the stimulant.

For high schoolers, drinking caffeine consistently may provide benefits but cause concern in the long term. “Your body kind of adapts to it so you have to take more and more and more. If you start taking it really young or as a high schooler, by the time you get older, you need it a lot. Typically people will have a cup of coffee and then as they get used to it, they probably need higher and higher caffeine amounts through energy drinks,” EHS athletic trainer Ravi Goldman-Henley said.

For high schoolers, drinking caffeine consistently may provide benefits but cause concern in the long term. “Your body kind of adapts to it so you have to take more and more and more. If you start taking it really young or as a high schooler, by the time you get older, you need it a lot. Typically people will have a cup of coffee and then as they get used to it, they probably need higher and higher caffeine amounts through energy drinks,” EHS athletic trainer Ravi Goldman-Henley said.

Additionally, after further examining studies about energy drinks, Dr. Chen noted that research subjects were typically not adolescents. “If you look at the [CELSIUS] research studies, they do it on adults 24 to 30 years old, so all of those studies don’t apply to teenagers,” she said.

An article for the National Institutes of Health also explained that little is known about caffeine consumption among teens. Some researchers reported that excessive caffeine intake by adolescents can be associated with health effects such as irritability, nervousness, and cardiovascular symptoms.

“It causes jitters and anxiety and stuff like that,” Goldman-Henley said. “More caffeine does not equal better, but there is evidence that caffeine does help.”

Many students reported experiencing these symptoms after drinking caffeine throughout their high school careers. “I definitely sometimes feel shaky after I don’t eat or drink enough. I’ve noticed a crash,” Schermer said.

However, even Strauss has experienced similar effects despite the later introduction of caffeine in her life. “I can tell when I’ve had too much, I get shaky and jittery––my heart rate increases a lot,” she said. “It’s like kind of a sweet spot, I need to have some, but if I have too much, then it’s just not worth it.”

Although Strauss is no longer a student, she acknowledges that caffeine played a vital role in her life during college and even today. “[In college] it did give me more energy to get through the day. I was definitely very, very tired, and now I still work and coach every night, and in between that, I try to fit in running or lifting weights. I’m energetically pretty spent and I feel like that kick in the morning to get me going has been helpful,” she said.

An integrated support: Athletics and activities dependence on caffeine

Students involved in athletics and other extracurriculars also find comfort in caffeinated drinks to sustain them. “I drink energy drinks, so a lot of CELSIUS [and] Red Bull. I don’t have a favorite, just anything caffeinated and fizzy,” Shipp said. “I do debate and I feel like there’s a big caffeine culture surrounding that. I think it’s pretty common to see people drinking multiple energy drinks.”

To not tire out during debate tournaments, which can last over 12 hours, Shipp drinks three or four caffeinated drinks a day. “I know it’s a stimulant, and sure I’m worried about getting addicted, but I feel like if it’s occasional, like, once per week at a tournament, it’s a special treat,” she said.

As an athlete, sophomore Jada Dahlin also feels that caffeine is necessary for improved performance. “I started drinking caffeine regularly in March because I have to wake up really early for softball. I usually would have one in the morning because we’d have tryouts and practices at like six in the morning. I would have one at nine and then I’d have one at lunch,” Dahlin said. “I feel ready to play and more aware.”

As an athlete, sophomore Jada Dahlin also feels that caffeine is necessary for improved performance. “I started drinking caffeine regularly in March because I have to wake up really early for softball. I usually would have one in the morning because we’d have tryouts and practices at like six in the morning. I would have one at nine and then I’d have one at lunch,” Dahlin said. “I feel ready to play and more aware.”

For athletes, caffeine improves their endurance when used in doses of 1.4 to 2.7mg per pound of body weight.

“The research on caffeine says that [it] makes athletes’ performance improve in short bouts. Too much caffeine makes you jittery and worse, but when you look at the studies they show it increases short bouts of high energy with an increased focus because it’s a stimulant,” Goldman-Henley said.

Additionally, how a person metabolizes caffeine may change their response in performance. Genetic variations in the enzyme that determines caffeine metabolism can allow some athletes to perform at higher rates for longer periods.

Goldman-Henley commented that many students overestimate how much caffeine their bodies can handle. “I think high schoolers take way over the daily limit that’s recommended by nutritionists,” he said. “I had an athlete drink too much caffeine before a game and he was puking and got jittery. If you take a lot of caffeine it can mimic concussion symptoms, if that makes sense.”

Dr. Chen also noted the misleading information surrounding athletics and energy drinks. For example, while CELSIUS claims to “boost metabolism,” it may not be effective on teens, and it may only work under certain conditions. “What they don’t tell you is that if you just give those drinks to people without the exercise, it does nothing. It’s not just that you’re drinking caffeine [from] a CELSIUS and your metabolism is going to do better, it’s with exercise,” Dr. Chen said.

As a result, Strauss neither advocates nor discourages caffeine usage for the athletes she coaches. “For my swimmers, I don’t necessarily recommend caffeine just because they’re all in middle school and high school. But, I’m not super against it. I know a lot of them drink BUBBL’Rs or coffee or CELSIUS,” she said.

From personal experience, Strauss finds caffeine consumption beneficial for her athletic performance. “I think the only negative was that [drinking coffee led to] becoming kind of reliant on it. If I’m training for a marathon or half marathon, I have to have my coffee before my long run,” she said. “It’s not a bad thing, necessarily, it’s nice when I wake up and that’s kind of how I get myself going. I eat, I drink my coffee, and then I’m ready to go out for however long.”

Strauss sometimes uses electrolyte supplements instead of drinking caffeinated drinks while exercising. “It makes it difficult if [caffeine] isn’t available to me on race day or on a day when I’m doing a long training run, and I just don’t feel great,” she continued.

Some student-athletes who consistently use caffeine to supplement their performance do not see how they may perform well without caffeine. “I would say it depends whether I’d play [better or] worse without caffeine before a game,” Dahlin said. “I feel like it’s a routine now, I usually have a BUBBL’R before a game, so I don’t really know.”

“I think that drinking caffeine is integrated with being an athlete. I just feel like it benefits you and it’s fun. I haven’t heard anybody say it’s like too much or ‘you’re too hyper,’” Dahlin said.

Students who use caffeine to supplement their abilities as athletes or in other various activities find it easiest to implement their own controls on their caffeine intake. “I’ll do a caffeine cleanse once a month. It’s like the worst week of my life, but that’s how I deal once the debate season ends,” Shipp said.

Goldman-Henley recommends that students take the time to explore how caffeine affects their performance before fully integrating the stimulant into their lives. “Some people drink a lot of caffeine and get used to it, but if you don’t drink caffeine, I wouldn’t just start with a huge energy drink. Then you get jittery and anxious,” he said. “Listen to your body.”

This piece was originally published in Zephyrus’ print edition on April 18, 2024