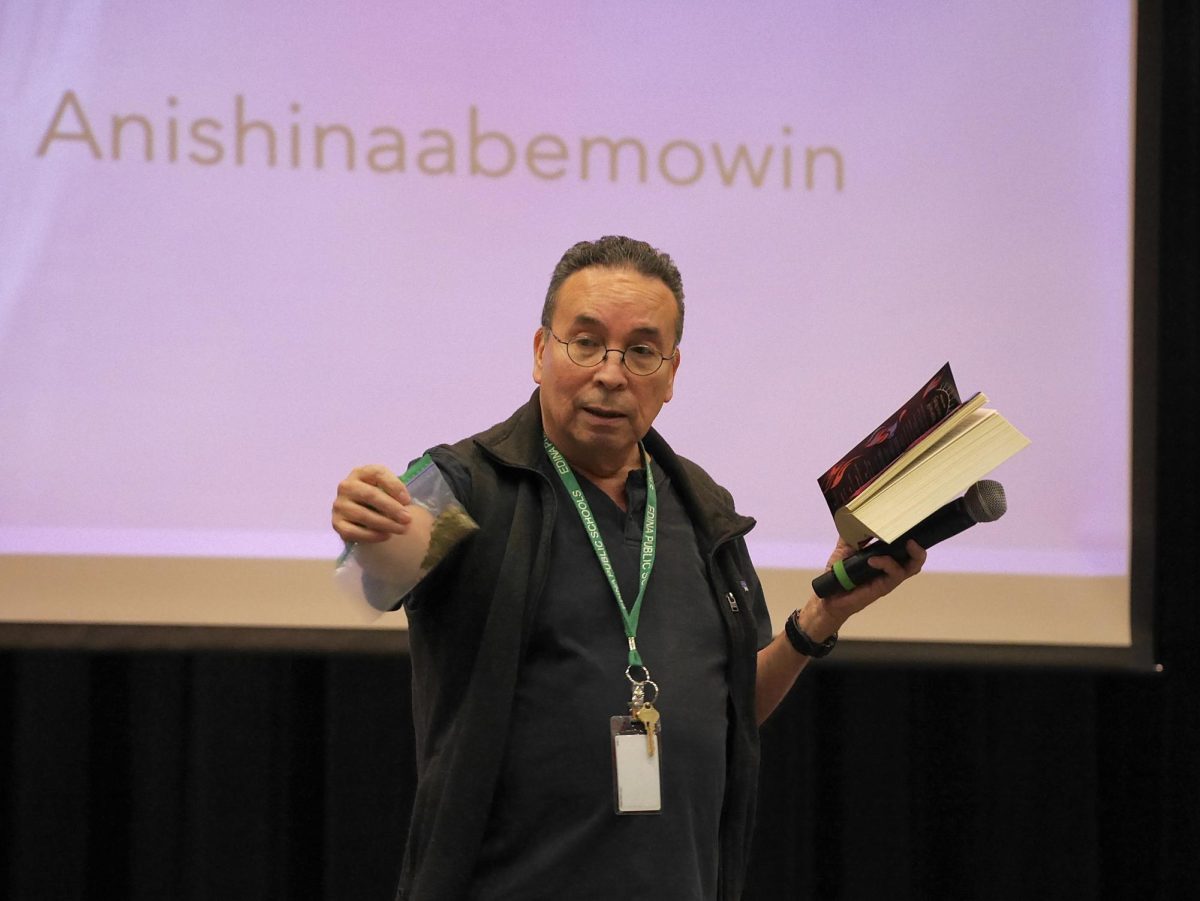

Duane Huisentruit always keeps a story in his pocket. His baggie of kinnikinnick—a fragrant combination of tobacco, dogwood scrapings, and bearberry—is a traditional mixture used in American Indian daily life and it never leaves his person.

For Huisentruit, though, it symbolizes more than his Ojibwe culture; the kinnikinnick represents the self-reckoning he faced when embracing his heritage. Although the baggie is mainly taken out for spiritual ceremonies, lately, Huisentruit has been using it for another purpose: to teach Edina High School students about Ojibwe traditions and his own cultural journey.

“I was taught that I have to carry tobacco with me all the time: for prayer, to put on a base of a tree, to put on a rock, to smoke—to use all the time,” he said to the class.

Huisentruit, who is half Ojibwe, joined Edina Public Schools this year as the district’s first-ever full-time American Indian cultural liaison. Early in the year, he expressed interest in teaching students about Ojibwe culture and Anishinaabemowin, the indigenous language spoken by Ojibwe people and the broader Anishinaabe indigenous group. Soon after, the EHS English department arranged for him to visit English 10: Roundtable classes on Jan. 23, when sophomores taking the course began reading “Firekeeper’s Daughter” by Ojibwe author Angeline Boulley. Huisentruit’s presentation interwove instruction on pronouncing Anishinaabemowin words, information on Anishinaabe ceremonies, and analysis of the first paragraphs of the book the students were reading. He used his personal experience connecting to his heritage to convey Native American values.

Huisentruit spent a childhood distanced from indigenous culture. He and his siblings were delegated to different foster homes when he was an infant because of their parents’ alcoholism and abuse. The family Huisentruit and one of his brothers grew up in was white and Catholic. Although Huisentruit maintains gratitude toward his foster family, he stated that it was difficult to manage a split identity and drew comparisons between his childhood and Native American boarding schools that existed to “Americanize” children in the late 19th century.

“[I had] an identity crisis. I looked in the mirror and realized that I’m not like these people. I realized that… they’re not teaching me anything about being Indian,” Huisentruit said.

When Huisentruit turned 18, he enrolled in Omaha Bible School. He was a Christian missionary until he was 27, when he met an Anishinaabe medicine man by chance. The man became his mentor, helping him integrate into the Ojibwe community in Minnesota. “I was introduced to different Indian ceremonies, like the sweat lodge and powwows,” Huisentruit said.

As someone who joined the Anishinaabe community in adulthood, Huisentruit learned spiritual ceremonies and earned his Anishinaabe name, Mashkode Inini (“Prairie Man” being the English meaning) later than usual. His fast, a coming-of-age event for Anishinaabe boys where they’re left in a forest for four days, was a trial that solidified him as a member of the Ojibwe community. “The significance is that every young boy would go out into the woods and experience the same thing of being helpless and [dependent] upon creation for their survival,” Huisentruit said.

Huisentruit’s Catholic beliefs faded away as he became a familiar member of the Ojibwe community. He began writing poetry about his spiritual journey and exploring Native American literature. Decades later, he took up the opportunity to become a cultural liaison for EPS to offer support to Native American families. According to Huisentruit, the Native American community in Edina is larger than most people think. “There’s 80 some families, really,” he said. “It’s a needed position.”

Huisentruit said he is happy to share his culture with others—his rounds through the English classrooms are an example of this. When he presents to them, he passes around tangible items like an Anishinaabemowin dictionary, a worksheet on pronouncing Anishinaabemowin vowels, and the kinnikinnick, aiming to immerse students in Ojibwe language and tradition.

Sophomore Wren Alexander said Huisentruit’s story and presentation enriched and humanized her understanding of Native American culture. “I feel like it gave more context to… the culture,” she said. “Just learning about culture in World History or something, you don’t really have a full grasp on how personal it is to people.”

English teacher Hayley Guevara assents. “There’s a disconnect between what we read and what we think is a real, lived experience. And so when we have…a person talking about being a member of a tribe, suddenly it’s not a book anymore,” she said. “It’s an actual human experience.”

Huisentruit will give the presentation again later on in the semester, when the sophomores taking English 10: Survey read “Firekeeper’s Daughter.” He hopes that the students take away the same thing: that Native Americans are not stuck in the past, but are rather engaged in a modern fight to keep the stories of their ancestors alive. “What’s important is that we realize that the Ojibwe people are still here,” Huisentruit said. “They still live in the community, and they’re still speaking this language, which is a living language.”