When washing their hands after using the restroom, some people face a seemingly trivial experience that is the amalgamation of decades of technology developing with one major flaw—racial bias.

Oftentimes, people forget the mechanical developments that have become increasingly integrated into our lives. We think about artificial intelligence, automated vehicles out of science fiction novels, and sentient robots of the future. But we need to focus on the past in order to hone those technologies and make them the best they can be.

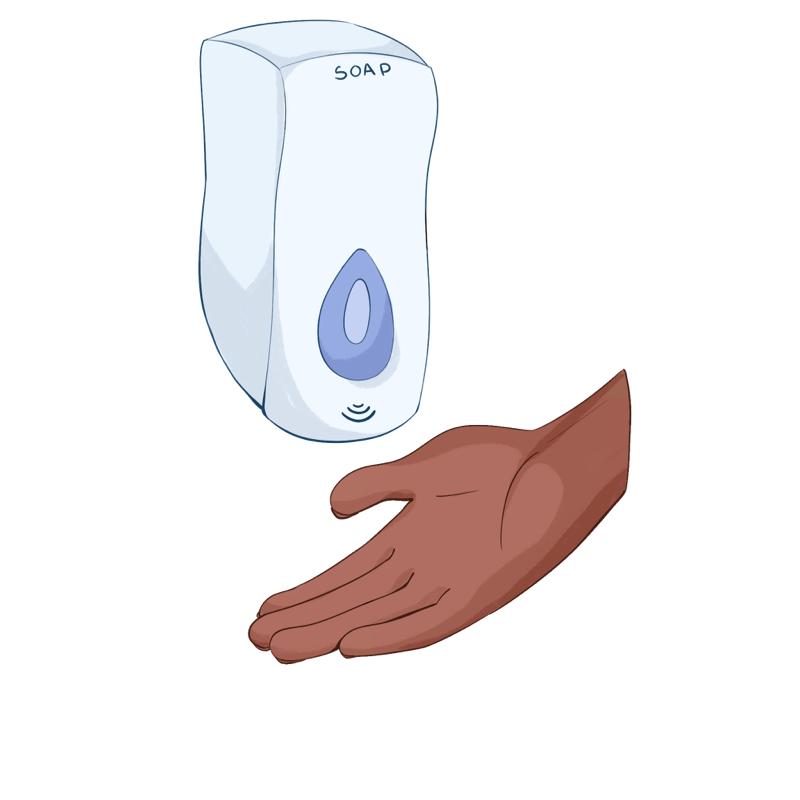

In 2017, a video of a Nigerian Facebook employee’s experience using a soap dispenser in the bathroom went viral after the machine failed to dispense any product onto his skin. Meanwhile, when a white coworker used the same dispenser in the video, the machine worked perfectly fine. Videos like these have popped up across the internet over the past few years, always showing the same issue; motion-sensor technology falls short when faced with recognizing people with dark skin.

I personally face this issue using public restrooms daily. Motion-activated sinks, soap dispensers, and hand dryers—the like. I spend more time waving my hand in front of a blinking red light than actually using those devices. How can we make technology that suits all of our needs if the devices we have today can’t do that on their own?

First, let’s break down how the soap dispensers in these videos work. Motion sensors don’t actually see humans or movements; instead, they use near-infrared technology and are activated by light shining onto the skin and reflected back to the dispenser. In a 2022 study, 30 cards with the six skin tones of the Fitzpatrick scale—a scale of different skin colors used by dermatologists to assess skin pigment and measure a person’s risk of skin cancer—were presented in front of an automated restroom faucet. The results showed that the darkest skin type did not trigger the dispenser most of the time because darker skin absorbs more light than lighter skin.

Of course, this study has its limitations. A printed piece of paper with only six different shades of skin hardly encompasses everyone. Still, the general idea remains. The lack of representation of people of color in the tech world leads to issues in the development of equitable technology. White men dominate companies, data sets perpetuate systemic racism, and, like the soap dispenser, a technology designed for healthcare is not created with people of color in mind.

In the U.S., Silicon Valley tech giants have tried to make big changes to diversify their workforces in recent years, but even Apple’s most recent report points to a workforce that is 42.1% white, 29.8% Asian, 9.2% Black, 14.9% Hispanic/Latinx, 3.2% multiracial, and 0.7% Indigenous. Google’s 2023 report shows that there are significantly more Asians in their company but also disproportionately low numbers of other non-white groups with demographics of 5.6% Black, 7.3% Latinx, and 0.8% Native American in their U.S. workforce.

These numbers don’t indicate the amount of people of color with leadership positions in these companies, however. A study by the Center for Employment Equity of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst revealed that according to data from the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 2016, the 40% of white men who made up Silicon Valley tech firms held more than 80% of the executive positions. Even with the changes companies have worked toward in recent years, white men continue to control the tech industry and prevent underrepresented groups from gaining influence over the products the technology sector develops.

Another pressing issue that has come forward as automation development moves faster is biased data sets. Every product goes through the process of being tested on recipients before being rolled out to the public. This may entail test-driving cars or trial-running vaccines. Regardless, data that represents people from all backgrounds is vital to the development of products that interact well with all people.

In public health, AI systems have failed to refer people of color to support programs as they do for white people. The data they are trained with shows that people of color, who don’t receive the same level of preventative care, spend more on medical visits for the same illnesses as white people.

An additional study from 2022 analyzed 12 different healthcare studies that deployed machine learning algorithms and found that eight of them were racially biased because of the data sets the algorithms were trained on. This lack of information comes from poorly equipped health facilities in segregated neighborhoods that have prevented people from receiving specialized care, which leads to less access and usage of public care resources, and that in turn results in a plethora of myths surrounding healthcare for Black people. Coupled with information affected by scientific racism in modern healthcare—which has dehumanized Black people over centuries—racial biases have formed in data.

For example, our understanding of a “normal” pelvis shape is based on studies of European populations, which has led doctors to perform unnecessary treatments in an attempt to “fix” fetal progression in Black women. This has contributed to the risk of pregnancy-related deaths in Black women, with white women having a three to four times less likely chance of dying. Due to historical inequities, false medical information like this comes into fruition as incorrect data sets and perpetuates systemic racism, which machine learning uses to discriminate against Black patients and other patients of color. It’s truly a vicious cycle.

No matter how inconsequential soap dispensers may seem at first glance, they are one of many products that show the day-to-day effects of racial bias. In 2015, when an Apple Watch with a new heart rate monitor was presented, many were concerned about the technique Apple and its competitors used called photoplethysmography. A light pulse would be sent onto the skin and detected by a sensor to measure how much oxygen was in one’s bloodstream. Like soap dispensers, this reflection of light relies on how much a person’s skin absorbs that light. When the watch was first released, Apple compensated for this issue by shining a brighter light onto darker complexions. Still, this traded off with battery drain and ultimately resulted in a product that wasn’t equitable for people of color regarding health issues.

Similar to the Apple Watch, some technology (including various soap dispensers) will shine brighter or darker lights to combat this issue. But schools and other public spaces can’t always install the newest and most expensive technology. This is a great example of the disparities in the public health sector created by the tech industry, with a solution that has to come from tech companies themselves.

It’s dangerous to assume that technology is neutral and companies won’t continue to perpetuate discrimination against minorities in the public health sector. These tech companies need a diverse workforce to take note of these errors and prevent the introduction of technology with inequitable designs. The creator and original poster of the soap dispenser video, Chukwuemeka Afigbo, even wondered on Facebook if “[h]aving a dark skinned person on the team would have resulted in a better product.” To solve these problems, we must first hold these discussions to spread awareness and create a better environment for underrepresented students to pursue their interests in STEM. By funding resources and providing more opportunities for minority students, we as a society can move forward and prevent biases in technology from spiraling out of control.