Schools nationwide continue to feel the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic thanks to heightened levels of chronic absenteeism that have persisted this year. For a student to be considered chronically absent, they must miss at least 10% of the school year.

Data from the Minnesota Department of Education showed that the rate of chronic absenteeism grew from approximately 15% in 2019 to 30% in 2022. Although national trends show that absence rates have begun to dip—the nationwide chronic absentee rate in 2022-23 dropped 2% from the year before to land at an estimated 26%—the impact is still notable according to teachers.

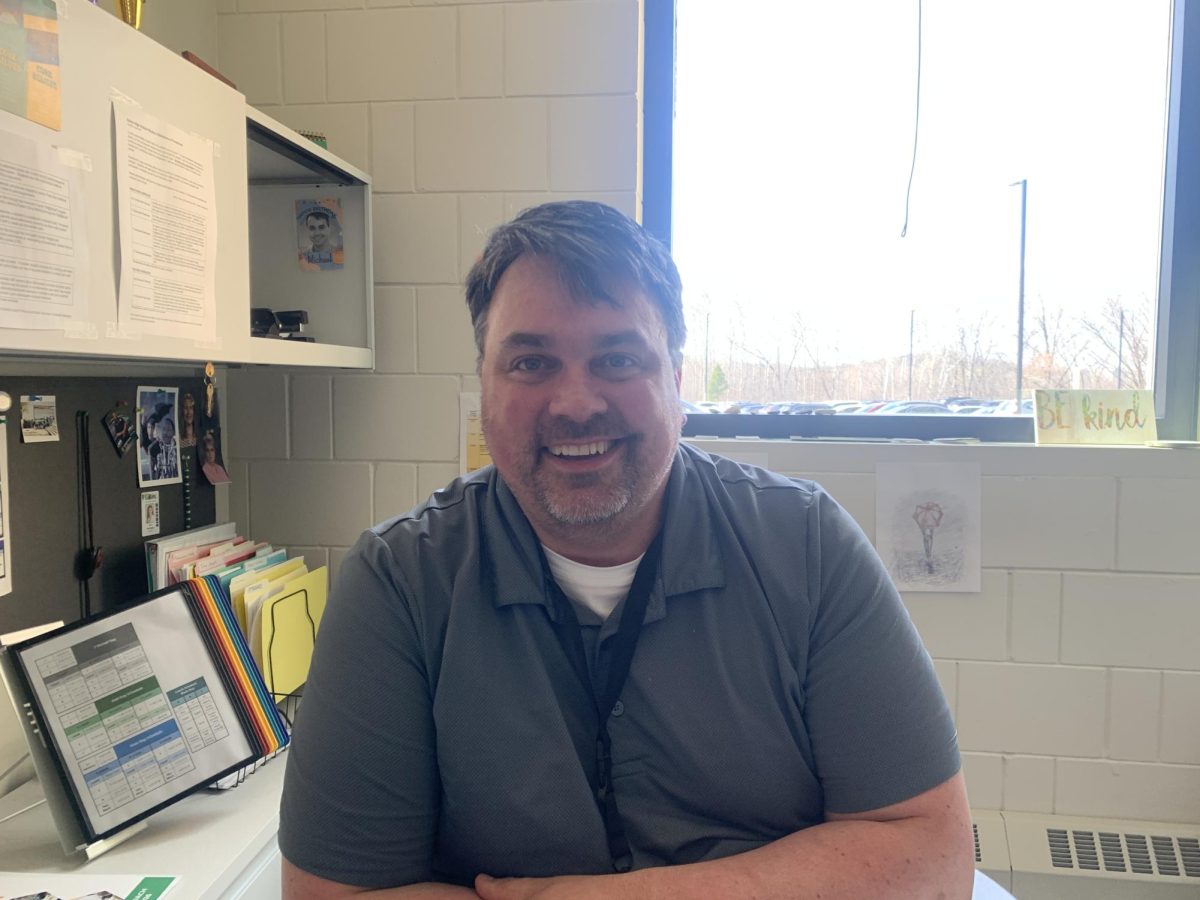

According to Edina High School math department head Nathaniel Murphy, overall attendance was worst immediately after COVID but it has improved since. However, he noted that the amount of chronically absent students has grown. “It’s not all students, but there’s definitely a group of students that are consistently either absent or tardy,” he said.

Multiple teachers noted that students don’t always see attending class as mandatory or even important. “I think maybe we’re still dealing with some of the mindsets, attitudes, and habits [of] COVID. There was one year when students could decide if they were going to come to school or do online learning,” said English teacher Teresa Bademan. “That was a necessity because COVID was in full swing, but I think we’re sort of cleaning up still.”

Science teacher Eric Burfeind emphasized that there are many valid reasons to be absent, but he said he has also noticed a shift in attitude toward attendance. “It used to be that school is school…and you don’t get to pick and choose when you can and can’t go,” he said. “And maybe part of that also is from the pandemic [because] we now have the week at a glance [on Schoology.] So students look at that and they say, ‘I can skip that class. I can skip that class. I don’t need to be there for that.’ So they’re just choosing their own schedule. And again it’s not the majority of students, but there are some.”

Chronic absences cause students to fall behind. One study showed that missing 10 classes can result in substantial reductions in grades and test scores. “If [students] are not in school, they’re not learning, they’re not turning things in, their grades are suffering. So there’s a real connection,” Bademan said. “Students who aren’t doing well in a class because of attendance are just reaping what they’ve sown by not being in school.”

Students don’t just miss out on classwork when they are absent. “The stuff that happens in class is more important than just [if] you got a good grade on the test. It’s all the stuff that students said they missed during the pandemic, interactions and engagement and being in conversations…and you can’t replicate that. So you can ace the exam, but you’ve missed the material,” Burfeind said. He also noted that students who miss class frequently often show less depth of knowledge.

Chronic absenteeism burdens teachers, who are responsible for helping students catch up. “If [chronically absent students] fail, then the question gets asked, ‘Well, what did you do to support those students?’” Murphy said. “The pressure gets put on me to make sure that those students are [doing] their missing work. And then traditionally, those students are the ones that are struggling because they’re missing lessons, they’re missing assignments, they’re missing lectures so they just get further and further behind and it’s just this vicious cycle. We invite them in for Flex, and if they don’t show up for Flex, then it just continues to be a problem of, ‘How am I supposed to get this student caught up when they’re not here for class and they’re not here for Flex?’”

Burfeind said that he often has students coming in at different times to make up assignments they were absent for, creating a hectic schedule. “Your brain is in all of these different places all at once while you’re also trying to say, ‘What am I doing tomorrow with everybody else?’” he said. “So it becomes a workload issue [because] I want to give every kid an opportunity, but it just becomes hard to manage.”

Per school policy, students are to be placed on an attendance contract after three unexcused or nine total absences. If they have another after that without a valid reason, the student is supposed to be dropped from the course. Although EHS admin hoped this policy would discourage students from skipping class, Murphy said this strategy isn’t always effective. “The hard thing is if there’s so many students that are at a place where they should be on attendance contracts, it gets hard for the office to manage that.”

According to Murphy, starting from the “top-down” by having the administration encourage teachers to record attendance properly could help the situation. “It’s our responsibility to make sure students realize that this isn’t a buffet, where you just get to pick and choose which days to come to class and which days are important and which days aren’t important,” he said.

Bademan, Burfeind, and Murphy all agree that every day of class is important, even if students don’t see it that way. “We need a culture change around attendance,” Bademan said. “We need students to…buy in and understand the relevance of their learning and the importance of building those connections with peers and teachers.”