Prevention, pursue, and protect: Hennepin County responds to opioid crisis

When Minneapolis resident Michelle Hein lost her son to fentanyl poisoning in the July of 2020, she knew she had to join the struggle against the opioid crisis.

“Two years ago, I decided to do something to help the crisis and hopefully save some lives so that [other] moms don’t have to feel the way I do every single day,” Hein said.

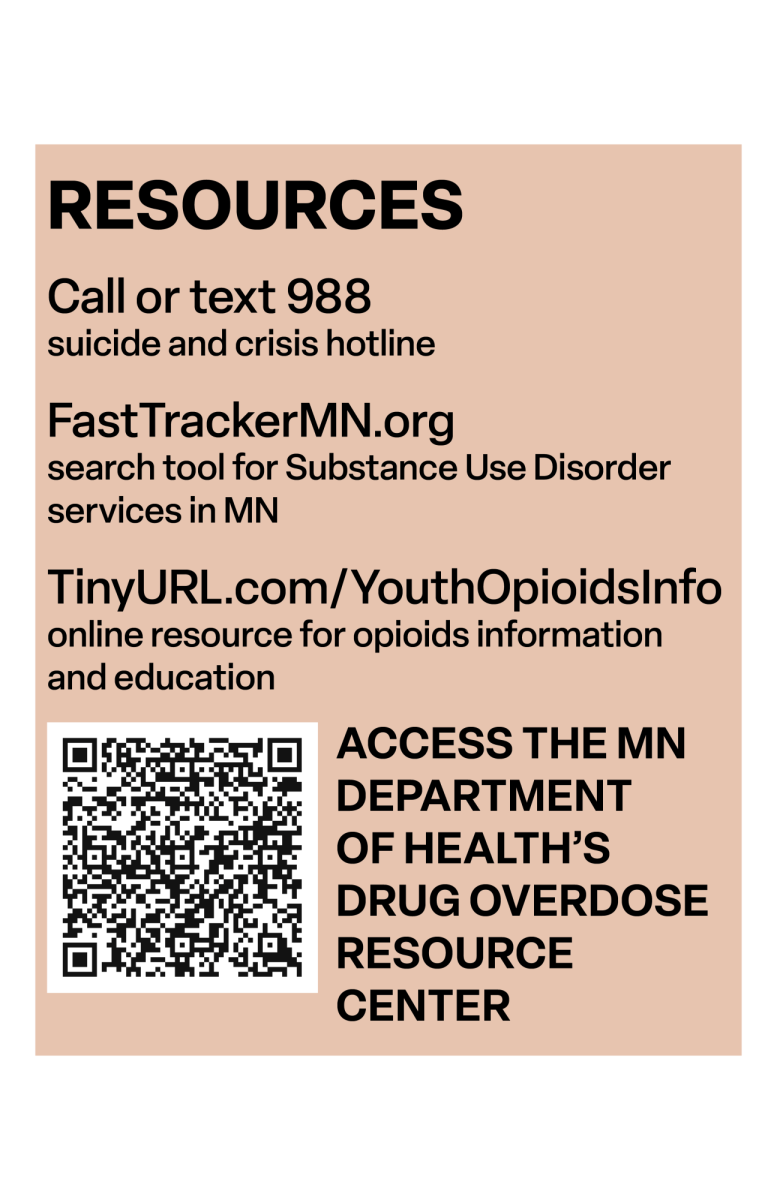

As current chairwoman of the Fentanyl Free Communities Foundation, Hein participated in the Opioid Summit on Dec. 5 with several other organizations and Hennepin County law enforcement. Presented by Hennepin County Public Health, the event included several professional-led presentations surrounding the opioid crisis and included free naloxone training for attendants.

Even with several residents in attendance, Hein said she still believed they did not reach their target audience.

“We’re preaching to the choir,” Hein said. “What that means is that everybody [in attendance] knows that we’re in a crisis and has been battling it for many, many years.”

In 2023, Hennepin County hospitals received 10,650 opioid-involved visits, the highest the county has seen in the past 10 years. And while the number of opioid-related deaths have dropped from 377 to 373 between 2022 to 2023, Hennepin County law enforcement has furthered its plan to respond to and reduce the prevalence of the crisis.

Minnesota has a troubled history with drugs. Between the 1900s and the early 2000s, methamphetamine ruled the drug scene. Hundreds of meth labs were found in Minnesota, containing dangerous chemicals that could explode if not properly cared for. Then, other drugs—cocaine, heroin, and marijuana—took over. Funds distributed from former President Ronald Reagan’s “War on Drugs” campaign provided 1.7 million dollars of funds to law enforcement agencies, including those in Hennepin County, which used the funds to instill drug prevention strategies in the past. However, according to Rafael Mattei, Assistant Special Agent in Charge for the Drug Enforcement Agency Minneapolis office, methamphetamine is starting to make a comeback.

According to Tim Stout, Chief of Staff for the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office, drug manufacturers have started to mix fentanyl with other illicit substances to produce a stronger high at a cheaper price. The mixture of fentanyl with other substances can hide the evidence of fentanyl within the drug, causing accidental overdoses when drug users believe they are using an authentic drug.

Additionally, since fentanyl is cheaper to produce, drugs laced with the substance are more accessible to minorities, according to Hennepin County Sheriff Dawanna Witt.

“[The current crisis isn’t] something new,” Sheriff Witt said. “It’s not different, [but fentanyl is] more impactful.”

Sheriff Witt views the enforcement of Minnesota’s drug laws as essential. The Sheriff’s Office has deputies who are assigned to various divisions within the department that focus on finding drugs. One such unit is the Violent Offender Taskforce (VOTF), a specialty unit designed to track down suspects who could be violent. On Nov. 26, VOTF conducted a raid of a home in Brooklyn Park, discovering a lab that was producing a hallucinogenic drug known as DMT. The chemicals that are used to produce DMT are highly dangerous to the health and safety of residents, according to the Sheriff’s Office.

The Edina Police Department is also a member of the Southwest Hennepin Drug Task Force—a collective of detectives from various law enforcement agencies who investigate drug offenses.

Local law enforcement is often limited in the scope of its investigations, according to Stout. This is because drugs, such as fentanyl, come in through the southern border and are often trafficked through major cities, such as Chicago, before arriving in Minnesota. Since this crosses state lines, it requires assistance from federal law enforcement, Stout said.

“There is so much collaboration going on between local and federal authorities right now,” Sheriff Witt said. “We have to work together to be successful.” According to statistics from Mattei, in 2023, the DEA seized 80.5 million fentanyl pills.

Law enforcement agencies, such as the Sheriff’s Office, have begun cracking down on dealers of fentanyl, now charging dealers for murder in some circumstances. “For our office, if we catch a dealer who was dealing fentanyl and it resulted in someone dying, we will submit a report and charges for a murder or attempted murder,” Sheriff Witt said.

The day prior to the Opioid Summit, Sheriff Witt received a voicemail from a mother of a Hennepin County jail inmate. She asked Sheriff Witt not to release her son due to his addiction to fentanyl.

“His mother feels more safe and more calm that her son is in our jail than she would if he was out in the community because of his addiction,” Sheriff Witt said.

In following the establishment of Hennepin County’s community-wide drug prevention strategies, the Sheriff’s Office has also focused on intervention and treatment within their jails to support incarcerated addicts.

“I always tell people that what you see in your jail is absolutely what you’re seeing in the community,” Sheriff Witt said.

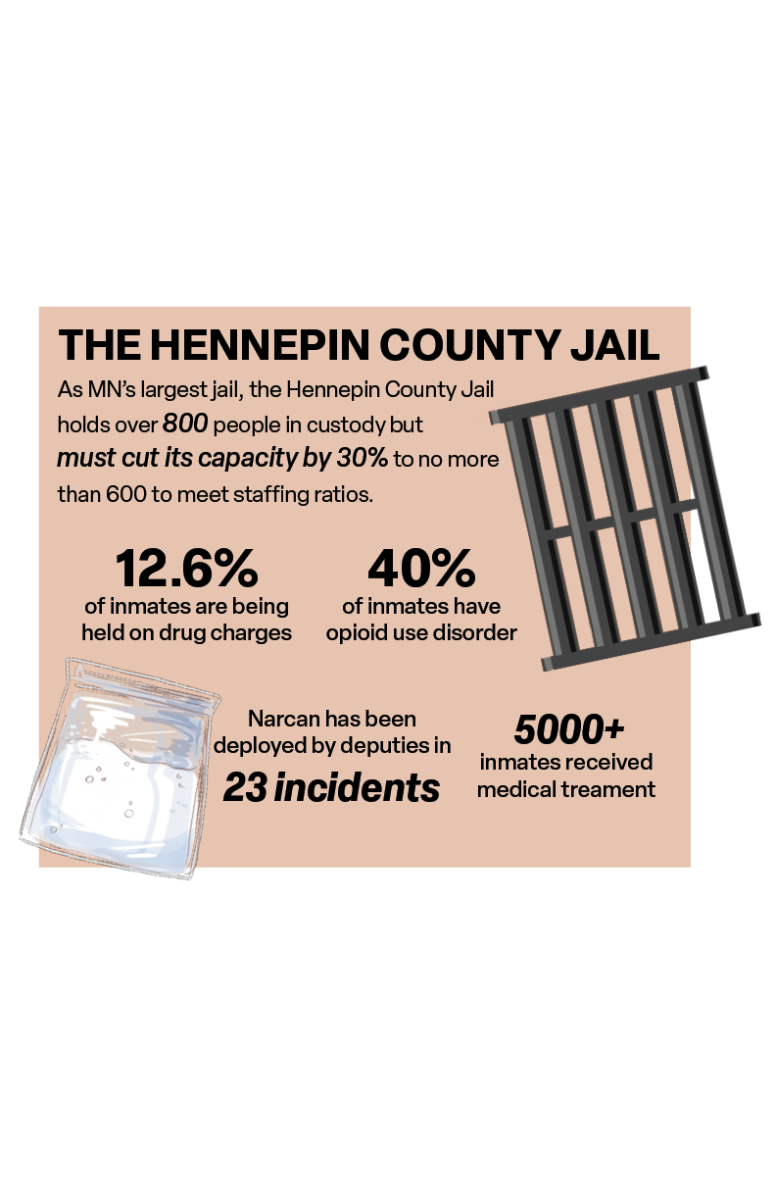

Hennepin County is home to the largest jail in Minnesota, with over 800 inmates being detained at any given time. At the time of writing, 12.6% of inmates held in custody are held on drug charges, the third most prevalent alleged crime. Approximately 40% of inmates in the Hennepin County Jail are dependent on drugs or alcohol, according to Jerald Westberg, the Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office Opioid Response Coordinator.

To address the high rate of incarcerated individuals who have opioid addictions, all inmates who come into the jail are screened as part of the booking process. “Everybody in our jail gets screened for opioid use disorder,” Westberg said. “Those who screen positively are given multiple paths for treatment.”

One path that is offered to inmates is medication that can be used to help fight opioid use disorder. Inmates, as part of the Medications for Opioid Use Disorder program, can receive free medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone.

“There are a handful of medications that have very high efficacy for treating opioid use disorder,” Westbridge said. “Very few jails in the United States offer [any] of these medications, but [Hennepin County Jail] offers all three, which is a rarity. Less than 10% of jails in the United States can offer comprehensive treatment for opioid use disorder…so our jail is really a leader in the criminal justice space when it comes to treating opioid use disorder.”

According to Sheriff Witt, 80% of people incarcerated in Hennepin County jails are returned to their communities, and as such, the jail must also focus on intervention and treatment programs. In addition to programs involving medication, the jail also offers mental health counseling and other resources for those struggling with opioid use disorder. “We have an abundance of programs for the [people] who need them,” Sheriff Witt said. “It is our job to make sure we give people the best care, whether it’s mental health [or] chemical health.”

While the facility hosts many programs that aid struggling inmates, the Minnesota Department of Corrections has recently scrutinized the jail. In a report filed on Oct. 31, the department alleged that it failed to maintain minimum staffing ratios and properly conduct well-being checks on inmates.

As part of the report, the Department of Corrections has ordered the jail to reduce its population by around 30%, allowing for a 1:25 deputy-to-inmate staffing ratio. The jail was required to comply with this order no later than Nov. 22. The Sheriff’s Office has since contested the order, but while the appeal is pending, has complied with the requirements of the order.

Despite the ongoing struggles, Sheriff Witt remains dedicated to providing treatment programs to the inmates of the jail.

“It’s non-negotiable,” Sheriff Witt said. “We have to continue to try to help people. We are charged for caring for those who are in our custody.”

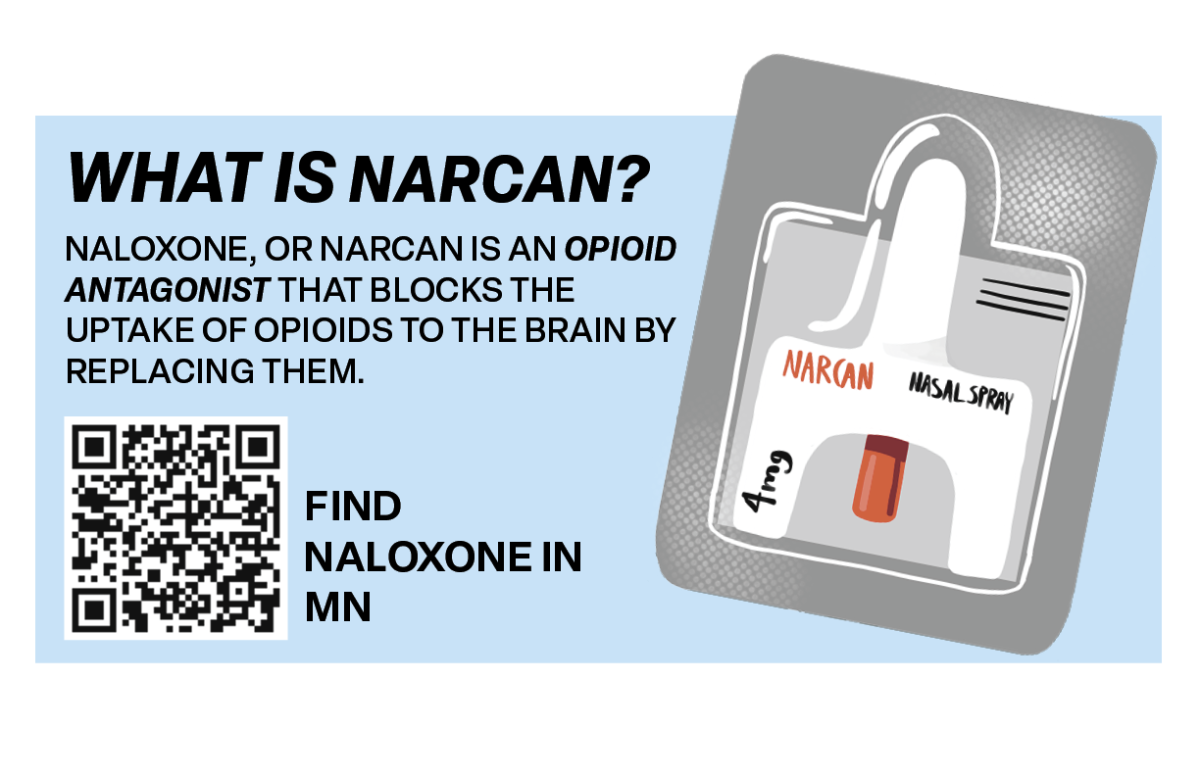

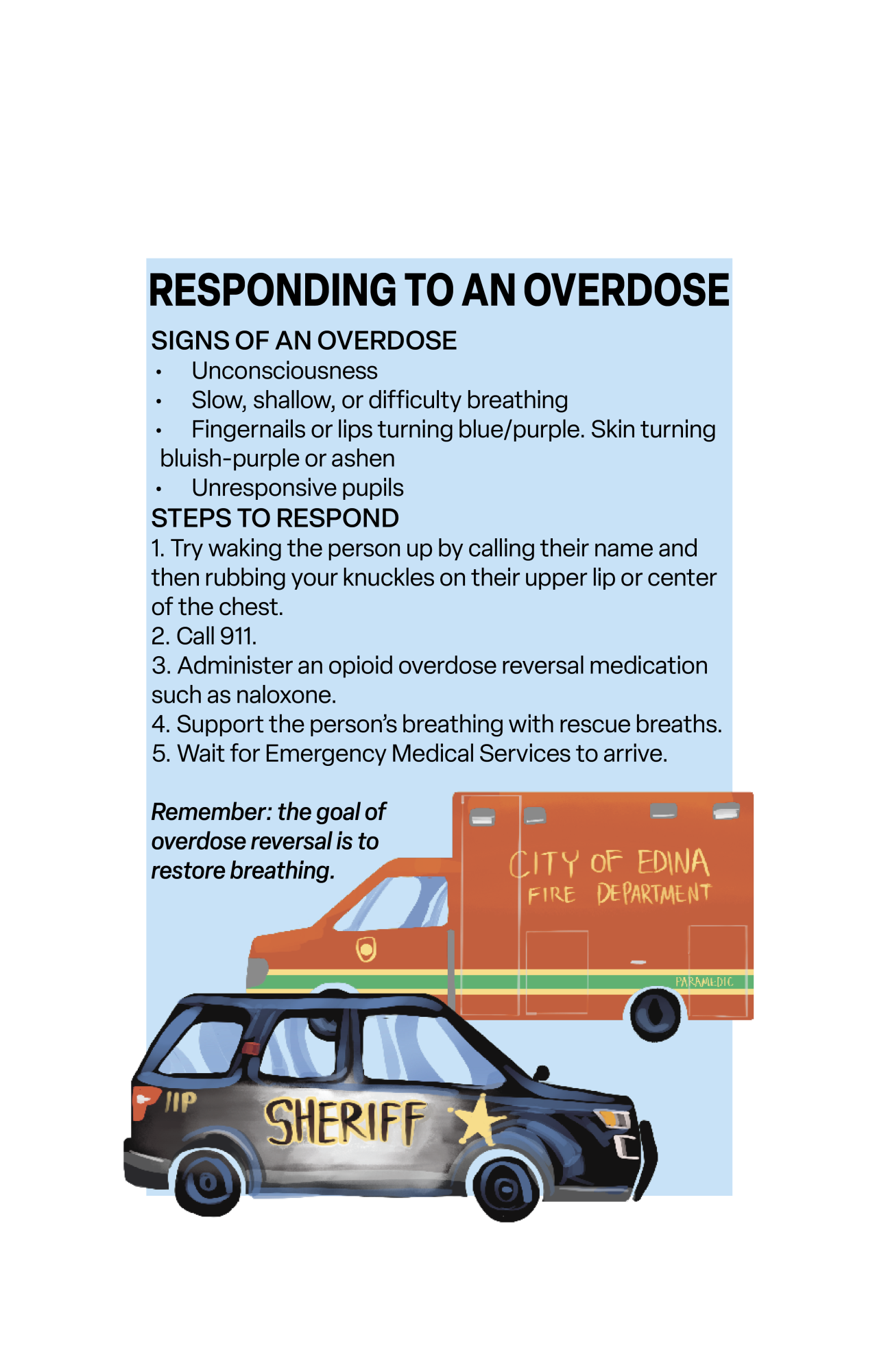

The jail has also taken measures to ensure that, once an inmate is released, they can continue to reduce their chances of an overdose. According to Sheriff Witt, inmates who are released from custody can have accidental overdoses as their tolerance from the drugs that they were addicted to decreased while they were incarcerated; if a person goes back to using the same dose that they were using before they were arrested, they can experience an overdose. In response, the Sheriff’s Office has started offering naloxone, commonly known as Narcan, to all inmates upon their release free of charge.

The jail provided treatment to 5,000 individual inmates in 2023, according to Stout. Sheriff Witt said she is optimistic about the programs available in the jail. “To me, if I can save one life, that is a success. That life is [a success],” Sheriff Witt said.

While Hennepin County law enforcement focuses on combating the crisis through intervention within jails and the wider community, the Sheriff’s Office must also contribute to a growing awareness of the crisis within the community, according to Sheriff Witt.

“It’s a crisis because of [a lack of] education. It’s a crisis because of the different means that it’s reaching our population.” Sheriff Witt said. “It’s a crisis because people think that this only happens to drug addicts, right? This only happens to people who struggle, but so there’s so much going on.”

In efforts to increase education surrounding the crisis, Hennepin County recently reintroduced the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program. Founded during Reagan’s “War on Drugs” campaign, the program intends to give elementary school children skills to resist peer pressure to use tobacco, drugs, and alcohol. Hennepin County police officers teach the curriculum directly to students, with a focus on educating fifth and sixth graders about potential peer-related pressures. New additions to the program include a focus on cyberbullying due to the increasing influence of social media on drug abuse.

After hearing the effects of the program from other Hennepin County officers, Sheriff Witt said she hopes she can expand the team to reach a wider audience..

“[Within our DARE program,] one of my deputies told me how a fifth grader said that they’ve tried a wide variety of drugs outside of alcohol and marijuana,” Sheriff Witt said. “[Opioids have] no limitation on age, so we have to keep talking about it.”

In addition to reintroducing the DARE program, the Sheriff’s Office implemented a youth sheriff’s advisory board to consider youth perspectives on the crisis. Sheriff Witt established the program in 2022 when she first obtained the role of Hennepin County Sheriff.

Advisory board member and senior Indra Khariwala said she believes the board can highlight more “discreet” issues within the school community.

“I think this board has allowed them to see the impact and existence of different issues that start in school settings or within friend groups at a lower level,” Khariwala said. “But that’s kind of where the problem starts, like with fentanyl for example, that can all start within friend groups, and then something goes wrong.”

Public events such as the Opioid Summit also provide opportunities for community members to become educated in resources and strategies related to opioid prevention. Although the target audience was not met, Hein said she urges people to continue discussing the crisis.

“Who we need in that room are people that don’t understand what the opioid crisis is and how deadly that is, and how prevalent it is in all recreational drugs,” Hein said. “You know, people sometimes think if you don’t talk about this, it’s not going to happen to me. Guess what? I didn’t talk about it and it happened to me,” Hein said.