The case to keep schools closed

September 5, 2020

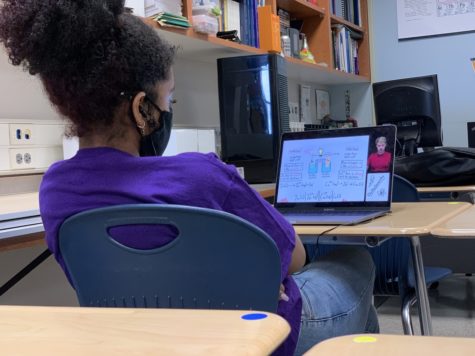

As summer comes to a close and Edina students begin to prepare for an unprecedented return to school, district administrators are working to implement a hybrid model with an option for completely remote learning. Superintendent John Schultz sent a school-wide email announcing the district’s hybrid model earlier this month, citing the “Hennepin County COVID case data” as justification for the partial reopening. The initial plan had students starting school before Labor Day, as was indicated on the predetermined schedule, but the date was recently pushed to Sept. 8 with the remainder of the week acting as an orientation. In earnest, school is slated to begin on Sept. 14 for all K-12 students in the district.

When the email was first sent out, I was slightly surprised; after Minneapolis had announced their commitment to e-Learning, I expected Edina to follow suit. Though I do think the administration is doing the best they can with the current information, it’s worrying that schools will reopen with 75-80% of students attending in-person, albeit on different days of the week and in limited capacity.

As of right now, all Edina schools are still expected to open in the fall; no announcements have been made that suggest otherwise. At an Aug. 24 school board meeting, board member Matthew Fox stated his intent to move forward with the hybrid plan, saying that “moving to a distance-only model and canceling hybrid is not even on today’s agenda.” I was disheartened upon hearing this—it felt dismissive of students’ concerns about returning to schools in the fall under a hybrid model. I had hoped that this ‘emergency meeting’ would be a larger discussion on the merits of focusing on distance learning and the Edina Virtual Academy program, especially after Bloomington recently decided to go fully digital, citing educational inequities and an increasing number of cases in the county.

If the school closes due to COVID-19 cases, it would ruin the opportunity for students who require hybrid learning and force them to only participate in a virtual model. I’m not arguing against a hybrid model; in fact, I think it’s necessary. For Edina residents who have young children, students with learning disabilities, or for those with an unsafe learning environment, hybrid is the best option. However, under the current model, all students have the option to learn in-person, and this lack of selectivity makes hybrid learning even more dangerous.

If the district had implemented guidelines and different criteria for students who would benefit the most from hybrid learning, the number of in-person learners would inevitably decrease and the schools would be able to more gradually increase the number of attendees. The criteria for hybrid could range from students already enrolled in special education programs, those who submit hybrid requests because of home issues, or any combination of things; the difference is that students would opt in to the hybrid model to more adequately address individual needs. Students who have the ability to learn safely and productively at home should only participate in distance learning to create a safe environment for students who lack those privileges.

Studies and surveys from the University of Minnesota show the racial disparities within COVID-19 hospitalizations. While Black residents make up only 6.8% of the state population, nearly a quarter of hospitalized patients identify as Black. As a predominantly white institution, the Edina High School administration must ask itself what concrete steps they’re taking to truly address systemic racism in the school system—and it starts with equity in reopening schools.

With that, Edina High School’s plans lack details critical to the health of students and staff. Passing time and lunch will become some of the most high-risk points of the day; how will students safely use the bathroom and walk to class during school? The smallest hallways can’t be more than 10 feet wide—that barely leaves room for two students to pass each other between classes. How will students who menstruate be able to safely discard any sanitary items?

I’m worried—not only for the students in the district—but for the custodial staff who will be exposed to contaminated surfaces every Wednesday, for teachers with pre-existing medical conditions, and faculty members who have become their parents’ primary caregivers. I’d love nothing more than to go back to class and feel as though everything was semi-normal. As a high school junior, I have to start seriously thinking about college, standardized tests, extracurriculars, and grades; but I can’t help but worry about the dire consequences of returning.

Palmer Monsen • Dec 18, 2020 at 1:36 pm

This is unscientific to be frank, studies show that schools are not a chief vector of transmission, according to multiple studies schools being open or closed have not had a major relationship with large covid outbreaks.

https://blobby.wsimg.com/go/104fc727-3bad-4ff5-944f-c281d3ceda7f/20201001_Covid19%20and%20Schools%20Six%20Month%20Report.pdf

https://biocomsc.upc.edu/en/shared/20201002_report_136.pdf